Lydia Jennings is a Yaqui & Huichol soil scientist and trail runner. She studies how to use plants and bacteria to clean the land from active mining sites, as well as understanding land management practices on tribal and federal lands.

Responses may be edited for clarity and brevity.

Where did you go to school?

- A.S. Biology, Cabrillo College, Santa Cruz, CA

Much love to community colleges! I had a wonderful time at mine — saved lots of money and was taught by incredible faculty.

- B.S. Environmental Science, Technology and Policy, California State University (minor: Chemistry), Monterey Bay, Monterey Bay, CA

I am proud to note that I worked full time while an undergrad, and though it took me a little longer than four years (six), I graduated with Honors.

- Ph.D. Environmental Science (in progress) (minor: American Indian Policy, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

What do you do right now?

I am a Ph.D. student and an environmental microbiologist in the Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Sciences at the University of Arizona. My minor is in American Indian Policy.

My research is in collaboration with three different mining companies to establish below ground parameters indicative of successful plant revegetation on reclaimed mine tailings. Mine tailings are the waste product of the mining process. They are finely crushed particulates (about the size and consistency of baking flour) that can easily get into the air; impacting air, water and soil quality of communities adjacent to mining sites. Historically, mine tailings have had heavy metals in them, causing a variety of negative health impacts. Modern mine tailings, such as the type I work on, are devoid of heavy metals, but the particulate size of the tailings can still be present health issues for neighboring communities.

We are working with mining companies to evaluate what they are doing to reclaim, i.e. clean up and stabilize, their mining waste. One method often used is putting a soil layer on top of the tailings to stabilize them and then establishing a plant cover to further prevent possible wind and water erosion. Because we are in an arid environment in southern Arizona, it can be a challenge to get plants to grow and become a self-sufficient ecosystem.

In my research, we are looking for correlations of plant cover with the below-ground microbial activity.

I look at a series of below ground indicators that include geochemical parameters like pH, electrical conductivity, carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratios and soil texture analysis; as well as biological parameters like DNA biomass (which is a general measure of bacteria, fungi, archaea and plant DNA) and fine-tuning which part of the microbial system is responding to the plant changes by using a molecular method: quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). I use qPCR to monitor the amplification of targeted segments of DNA, specifically, bacteria(16S rRNA bacterial gene) or fungi (18S rRNA fungal gene). The presence of this genetic material tells different stories about the below-ground dynamics that may be helping or hindering plant growth. We’re about four years into this project now, and we’ve begun to see some interesting patterns and promising trends… it will all be in my upcoming paper!

What made you choose your STEM discipline in the first place?

I’ve always loved being outside, whether it was playing outside in the mud, helping my dad garden or running around with my dogs. As I’ve gotten older, I still love to experience the environment through outdoor recreation, especially trail running.

These outdoor experiences helped strengthen my skills of observation and ignite my passion to ask questions of both teachers and elders about the natural environment.

This appreciation of being outside and understanding the natural environment is coupled with my commitment to serve marginalized communities.

As an undergraduate, I took a course in environmental justice. It was the first time I heard the academic terminology to identify what I knew was impacting tribal and hispanic communities that I grew up around.

It helped me understand the political influences of why our lands were being extracted — or why my mom and her family had worked as cotton pickers — and how it has had a lasting legacy that impacts their health. It was clear to me in this environmental justice class, where I worked with farm worker families on ways to reduce pesticide exposure through preventative measures, that

the purpose of my science needs to be to rooted in using data to empower communities. To me, science is as much about people and using data to serve them, as it is developing hypothesis, learning methods, and applying statistics to develop conclusions.

While I enjoy the practice and artistry that goes into being a technically strong scientist, I love understanding how my science can be applied to address issues that impact our more marginalized communities. I also believe that in this work of learning how to clean up mining waste, it’s important to educate the public about how much we are part of the demand-cycle for metals.

No one wants a mine in their community, yet we all love new laptops, cell phone, cars, etc. Most people haven’t seen a mine and don’t recognize the environmental, health and sociocultural impacts it can have on surrounding communities. This is why I always discuss the cycles of consumer demand and environmental impact as an important aspect of mining and soil science as much as possible, so we can understand the full implications of our everyday decisions.

What’s one piece of advice you wish you had when you started your STEM journey?

Everyone’s path is different — it’s okay if your educational or career trajectory is a meandering river — those are usually the healthiest ecosystems, and people who have meandering paths are, in my experience, the most powerful agents of innovation.

Do what makes you happy and don’t let the advice or limitations of others scare you away from the things you are passionate about. You will make your own pathway, and it will be beautiful.

Do you have any woman of color in STEM sheros? Who and why?

I have three academic sheroes that I’ve encountered during my PhD work:

Dr. Karletta Chief: A Navajo woman, hydrology professor, runner, mother and amazing human being! Dr. Karletta Chief is part of why I came to the University of Arizona. I saw her on my department’s website, and loved that her research was really focused on serving Indigenous communities, specifically her community, the Navajo Nation. She helped demonstrate to me that the University of Arizona, and my department, would be an excellent place to pursue the multiple interests I have. Since being here, I’ve been able to go out field sampling with her and see not only how impressive she is as a researcher, but also in balancing family, being present in her community, gaining tenure and still running! She’s #goals.

It’s really a blessing to have such an incredible Indigenous woman as a role model, in my own department, and develop a relationship with her. I recall a time being invited to her house for thanksgiving during a break that I couldn’t go home (during that time of year, I am usually processing field samples). She had a “Resiliency feast” at her house — something only a Native faculty member could appreciate and really make us Indigenous students feel at home in, while eating Indigenous foods! She is always working to serve Native students and create more opportunities for us and our communities. I am amazed by how much Dr. Chief accomplishes and she makes it look easy. I recall a tough time handling some criticism and asking her how she handles it: she said she channels negative comments as an incentive to prove the naysayers wrong. I take that advice to heart.

Dr. Marisa Duarte: A Pascua Yaqui professor in Arizona State University’s School of Social Transformation, who has a Ph.D. in Computer Technology and studies digital technologies as forms of social resistance and endurance. She also advocates for intellectual freedom and social justice in Native American and borderland communities. Though we are from the same tribe, I didn’t grow up in our community, so I first met her at the American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES) Conference a few years ago. I immediately felt kinship with her — we ended up talking for two hours that first meeting, sharing about our families, research interests and how unique our tribe is. Since then, she’s really been an inspiration in how to be a stronger Yaqui woman. On the academic front, she has really transforming how I think about technology. She is able to integrate activism into her scholarship in a way I really admire. I’ve been fortunate to see her a few times when she comes to Tucson for ceremonies and to visit her family.

I appreciate seeing a powerful, young woman from my own community doing such important work. I want to be like her when I grow up!

3) Dr. Elizabeth Hoover: A Mohawk professor of American Studies at Brown University. I love how her scholarship integrates three of my interests: environmental justice, public health and Indigenous communities. She’s written extensively about linking environmental justice to reproductive justice (such important work!). For her Ph.D. dissertation work, she worked with women in her Mohawk community who were downstream from a power plant. Using a community-based participatory research model, she trained female community members how to test their own breast milk, ultimately seeing a link in health issues with the proximity to an EPA superfund site nearby (the full story of this work has been written up in a beautiful book called “The River is in Us”). She continues to work on community-engaged research in food sovereignty of Indigenous communities, yet another area that I am interested in expanding my research towards. Her range of scholarship really inspires me.

All three of these incredible woman scholars are examples of integrating multiple passions into impactful scholarship that serves Indigenous people, while always making opportunities to support Indigenous students. They are also incredibly kind, giving individuals who have offered support during my Ph.D. process. I strive to be half the scholar they are.

What else are you passionate about?

I am passionate about the outdoors, outdoor recreation, running and living healthy, using art in science communication and using scientific data to support tribal sovereignty.

Recently, my friend Ashleigh Thompson and I have started a social media campaign to highlight Indigenous scholars called, @natives_w_aptitude. The goal of the account is to highlight the incredible range and caliber of scholarship present in Native communities.

We felt that in general, being Native American at universities can be an isolating experience, especially as graduate students. We want to use the platform to create kinship for other Indigenous scholars.

We are fortunate to be at the University of Arizona, where there is a fairly large Indigenous community — but what about students who are the only one at their university?

We love that the account can be an avenue for scholars to connect with one another, share their stories and their interests, and hopefully foster future collaborations! On the account, we feature a range of scholarship — not just scientists — and first and foremost, recognize that an advanced degree is not the only way of knowing. There are powerful knowledge holders in our communities, who may or may not have attended universities, but are nonetheless, experts. We have about three posts up, but are really excited about the future of the account.

Why do you think it’s important to highlight women of color in STEM?

SO MANY REASONS!!

One thing science has taught me is that anytime there is a homogenous population, it seems to not have a high survival rate. Heterogeneity provides room for more resilience.

This applies to the thoughts and ideas of individuals. The more heterogenous a workforce is, the more diverse contributions and solutions to our everyday problems we can begin to produce. That’s exciting and really works towards the benefit of all of society, especially developing new solutions to many of the problems our world has.

Having women of color in STEM helps break down patterns of how STEM has traditionally been rooted in colonization and patriarchy.

What does that mean? Many of the methods, many of the ways we report data, many of the ways we discuss populations have residual traits of colonization. We need to take a step away from that for the betterment of society and science.

Women of color in STEM amplify their own communities’ voices.

We need more studies on the health of Native communities, border communities, immigrant communities, black communities and trans- communities. The best way to do this work is have women from these communities engaging with their own communities, because they understand cultural dynamics in a way an outsider cannot. It is important that we have representation on all levels.

As I’ve been moving up the academic ladder, I see women who look like me, who are passionate about similar subjects and using their academic privilege to amplify their communities’ voices.

It ignites me. Education can be a challenging path, but it’s an important one. Seeing woman who share your experiences, who share you passion and your cultural background help expand the pathway for others. I’m grateful for the incredible women I have met during my Ph.D. process.

Are there institutions, groups or organizations you want us to mention in your feature?

There have been a lot of important programs that have helped me get to where I am today, and many people cheering for me to succeed! A few organizations that I’ve become involved in, include:

The Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS). This organization gave me life as an undergrad and an opportunity to meet many other inspiring POC in STEM.

The McNair Scholars Program helped train me to become a better writer, a better researcher and provided me with essential mentoring and financial support as an undergraduate. They also helped me navigate what applying to graduate schools was all about, so that I knew how to be a strong applicant for programs and fellowships.

The National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program has funded three years of my graduate work and opened up many additional opportunities for me. Because of this fellowship, I’ve been able to focus — full-time — on my research for the first time in my life.

The Sloan Indigenous Graduate Partnership Fellowship, which serves Native American students at the University of Arizona. I’ve met some of my best friends through the community this program provides.

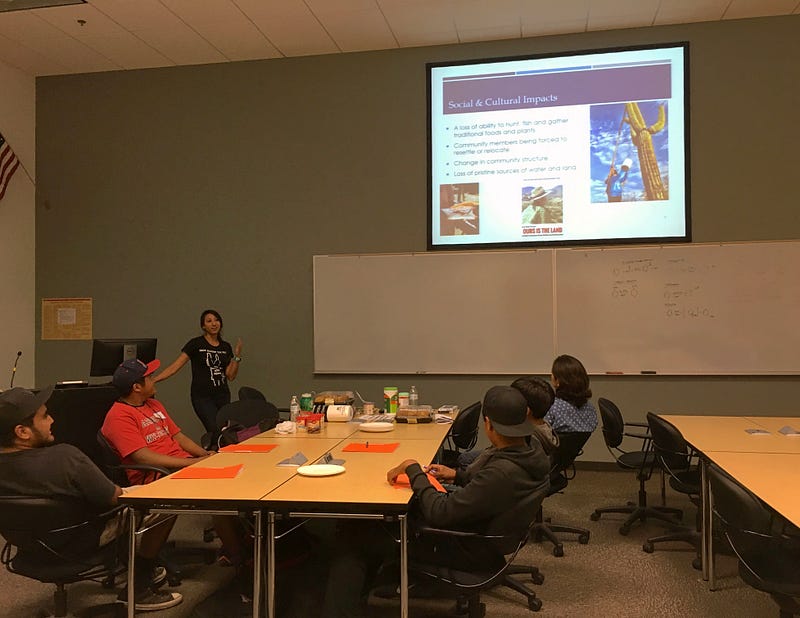

The National Institute of Environmental Health Superfund Trainee program (NIEHS) at the University of Arizona (@UASRP) has allowed me to pursue a range of community engagement with tribal communities that we work in. I really appreciate this component of my Ph.D. work, because it keeps me inspired as to why I pull late hours in the lab, and for whom.

Through the American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES), I’ve met so many inspiring Indigenous scholars from around the country, and have really benefitted from their leadership and mentoring training.

500 Women Scientists is an organization meant to support, mentor and mobilize women scientist.

And of course, a proud member of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe!

Is there anything else you’d like us to know?

I’m an ambassador for @NativesOutdoors, which aims to increase the representation of Indigenous people in outdoor sports and increase awareness of public lands as tribal lands, where tribal nations should be part of the land management cooperatives.

You can find Lydia on twitter, instagram and facebook.